By Grant Dutro

Warning: Spoilers and Some Allusions to Disturbing Content

David Cronenberg, admittedly, is a director I have some trepidation about. His films are notorious for their exploration of taboo concepts and bodily mutilation—take a peek at the synopsis of Crash (1996) to see what I mean. But Videodrome (1983) had been on my list for a while. Its reputation as a prophetic masterwork of media philosophy was too tempting to not indulge. Ironically, this quenced urge on my part meshes well with its messaging.

Videodrome follows TV network president Max Renn (James Woods), a hedonistic executive who scours the world for the most salacious content possible to boost ratings. He justifies himself by saying he’s providing a service to those who have forbidden desires, sating their thirst so that they do not act misanthropically themselves.

Renn stumbles upon a TV signal that he could never expect: “Videodrome.” The program is plotless in nature—all “Videodrome” portrays is a half-hour of torture and murder. And, as Renn soon realizes, it is not an act.

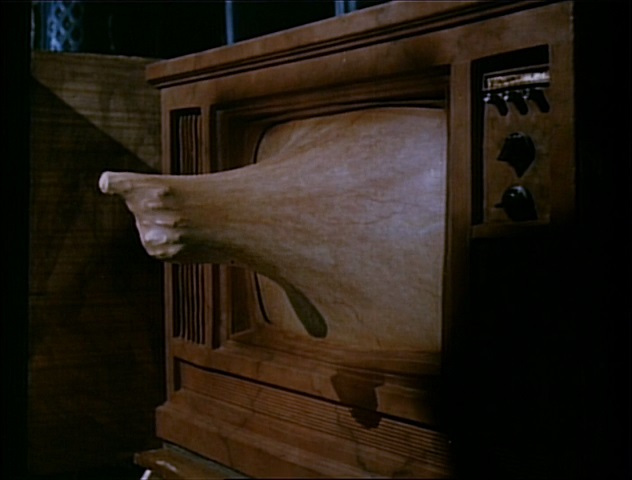

Renn’s discovery sends him on a hallucinatory journey that blends reality with broadcast television, flesh with the screen. In the process he encounters Professor Brian O’Blivion (Jack Creley), a deceased media theorist kept alive through tens of thousands of video tapes, and Nicki Brand (Debbie Harry), a sadomasochistic radio host who disappears after trying to get onto “Videodrome.” By continuously viewing “Videodrome,” Renn becomes plagued with violent, grotesque, and fleshy visions, usually surrounding his television

“Videodrome,” as Renn discovers, is a broadcast signal designed by and stolen from O’Blivion by an arms organization (likely the government). The signal causes brain tumors in its viewers to weed out and eliminate those obsessed with sex and violence: a means to avert cultural decay. Viewers can also be programmed by this entity. Further chaos ensues as Renn becomes an active agent on this digital battleground, and his obsessions with sex and violence quite literally alter his body.

Now what does such a twisted film have to do with faith?

Much has been said regarding Videodrome’s prophetic nature. Digital society and its intricacy allows for every potential urge to be indulged. Social media and online chats offer safe havens for those obsessed with sex, violence, and everything adjacent to discuss and receive affirmation—all masked in anonymity. As acclaimed film critic Walter Chaw writes, “The idea driving ‘Videodrome’ is that the moment technology allowed individuals to consume only what they wanted to consume, they would become intellectually frozen and ideologically perverse.”

The hallucination/body horror scenes of Videodrome have transfixed themselves firmly in pop culture regarding our grossly overdependent relationships with ever-proliferating technologies. And for good reason. Videodrome makes what we watch in the dark corners of the web physical in their effect. Let’s narrow this thought down to a single strand of the darkness: Pornography. Pornography addiction does not confine itself to satisfaction within the moment. One can’t be engrossed wholeheartedly in it one second and be authentically loving in a Christ-like manner the next. It bleeds into all aspects of our lives—spiritually, emotionally, and physically. In the same way that Renn, who is obssessed with the torture pornography of “Videodrome,” grows a living gun on his arm, these obsessions becomes part of us.

All of this is distinctly Huxleyan. For those unfamiliar with Brave New World, Aldous Huxley’s seminal 20th century novel describes a totalitarian dystopia where the populace is not subjected to the iron-fist authority of Big Brother. Instead, the people are subdued with entertainment, pleasure, sex, and drugs (especially one called soma). This “soft” totalitarianism (Rod Dreher, Live Not by Lies) maintains its ideological eminence not through force, but through numbing their people. The people eventually become so numb that they do not even want their personal liberties.

Late in the novel, leader of this dystopian society Mustapha Mond says, “Anybody can be virtuous now. You can carry at least half your morality about in a bottle. Christianity without tears—that’s what soma is” (Huxley 285). In the world critiqued by Videodrome—our world—technology affords us a soma-like cure-all for every unsatisfied desire we have. Worst, it redefines our morality to our own whims. Why suffer the constraints of seeing people as fellow image-bearers, of seeing the goal of life as to make Christ known and to know Christ, when you can create your own grace through a search engine?

The Apostle Paul replies: “Therefore, I urge you, brothers, and sisters, in view of God’s mercy, to offer your bodies as a living sacrifice, holy and pleasing to God—this is your true and proper worship. Do not conform to the pattern of this world, but be transformed by the renewing of your mind. Then you will be able to test and approve what God’s will is—his good, pleasing and perfect will.” (Romans 12:1-2).

Our tech-flooded world offers more avenues for temptation than we can possibly imagine. It’s paramount to understand that reorienting your morality around yourself will only leave you to be programmed by something else—sex addiction, violent behavior, Big Tech, whatever. After watching a film where people quite literally become the living embodiments of their perverted desires, the idea of being a “living sacrifice” for God—flooded with the light of His grace—could not be any more appealing.

Leave a comment